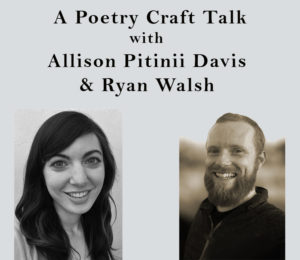

Baobab Press’s new literary imprint, Red Ochre, is devoted to elevating voices that rescript our conceptions of identity and place. The imprint launched with Allison Pitinii Davis’s 2017 poetry collection, Line Study of a Motel Clerk, a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award’s Berru Award for Poetry and the Ohioana Book Award. The collection examines a family’s century-long effort to make a home in a changing world, with all the grit, beauty and truth of the working-class immigrant struggle. This February, we’ll release Reckonings, the debut poetry collection by Ryan Walsh that interrogates the dissolution of American industry and rural community.

Since these collections share interesting thematic intersections, we recently asked Pitinii Davis and Walsh to sit down for a craft talk. They asked each other about place-specific poetry, about artistic inspiration, about the ethical implications surrounding their work, about the capacious power of poetry, and much more.

Ryan Walsh interviews Allison Pitinii Davis

Ryan Walsh: I want to ask about the title of your book, specifically with reference to the notion of a line study in visual art. Poetry offers ample opportunities to study line, and you do that so adroitly and with complexity (especially in “A Conversation with America About Small Businesses” which brings the reader’s attention to the various meanings of the word “line” itself). How do you understand “line study,” as an artistic method or way of seeing, working in this collection? Is there a particular perspective you wish to capture by this approach?

Allison Pitinii Davis: Thanks for these thoughtful questions, Ryan. The book’s earliest title was Line. From its conception, I was interested in lines of work, family lines, real and symbolic assembly lines, mathematical lines, and lines of poetry. I never met my grandfather—the Motel Clerk of the title—so the collection reconstructs him via his business, oral history, archival material, and my imagination. In some poems, lines build around his negative space until his outline emerges, and in other poems, the present serves as the end of the line and the poem reels—kite-like—back to him.

Much of the book is about immigration, diaspora, and post-industrial landscapes and argues that the mere outline of what’s been lost or taken has value. GM assembly lines become symbolic of American assimilation—the construct of nationality. Loss and preservation are formally enacted via caesuras, gaps, syntax, and jagged lineation—space holders and outlines of what has been lost. One reason I chose poetry for this collection is its capability to incorporate loss as a (sturdy!) building material.

RW: In one of your earlier interviews, you said that in shaping the book, you looked to the motel itself as a kind of inspiration—with each poem inhabiting its own numbered room. I love that! What other forms, artistic or otherwise, helped shape individual poems or the collection itself? I notice, for example, a few references to cinematic scope and Hollywood, as well as different types of craftsmanship gleaned from work done well….

APD: At readings, I love when people tell me that they grew up in a business and how the work translates to their current skillset and outlook. And neuroses. The first time I read Charles Reznikoff’s “Passing the shop after school,” in which the speaker wavers between pursuing books or entering the family business, my worlds merged.

The film references—like many poets, my first dream was film school until I learned how much it cost. But I still research it. In recreating the eras of the book, I researched intersections of art and popular culture—Northeast Ohio radio stations, bands, bumper stickers, and newspapers; the double-feature, movie-going culture of immigrant sweatshop workers; the evolution of light technology via traffic lights and neon signs. My aunt’s stories about working on the line and then going out dancing, my grandfather listening to the same Rachmaninoff symphony in his living room after work for years, my grandmother as a young girl staring at Clark Gable photos in the magazines at her brother’s shoe shine parlor, my non-observant grandfather’s insistence that his family see Fiddler on the Roof while visiting New York, my Greek great-grandmother surprising her grandchildren with the English slang she’d secretly learn from Hollywood Squares—and now, talking to truck drivers about my poetry book about the motel at the motel—the intersections of working-class culture and art endlessly compell me.

RW: As someone who has also delved into the working life and history of my family and a post-industrial town, I admire your decision to give some breathing space between your speaker and your intimately personal subjects via the decision to use the working roles people had rather than proper names. On the one hand, you write, “this / is how people get lost. In the thick of names.” And Line Study… is a collection “surrounded by actual women.” Yet we often have the dramatic distance of roles (The Motel Clerk’s Wife, The Laundryman’s Wife, The Merchant Marine’s Daughter, etc.). How did you navigate the terrain of writing what is essentially your family history, as well as providing a view into the story of a specific place and time?

APD: I’m interested in your own response to this question. For me, identifying people by their occupations was both a way to protect my family’s privacy but also to stay true to the culture—I think for people in family businesses, what you do for a living becomes, for better or worse, inseparable from living. The occupational titles were also a way to emphasize how jobs were handed down within families—the generations change, but the businesses and job titles don’t, which is beautiful and stifling. In the book, the family businesses are the continuity against the backdrop of the deindustrialization of Northeast Ohio.

The occupational titles also have Jewish-literature precedents—for example, Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye The Dairyman and Bernard Malamud’s The Assistant and The Fixer. In these books, each character’s occupation fits him like a chess piece—it impacts how he moves through the plot, his powers and limitations, and how he functions symbolically.

RW: Throughout the collection, there are (not surprisingly) women holding the world together in so many ways—“smoothing and smoothing America / like some long cloth you’re pressing at your husband’s laundry.” Who are some of the women outside your family who hold the world together for you?

APD: Kathy Fagan Grandinetti, Sherry Lee Linkon, and Rochelle Hurt—their writing and commitment to their communities. Karen Schubert and Liz Hill of Lit Youngstown published oral histories of Youngstown women. I’ve been lucky to participate in and teach workshops, and there’s never been a female writer that I haven’t learned from, starting with Lo Kwa Mei-en from my MFA, who has revolutionized language forever. A goal this year is to catch up on the transnational Jewish literature and theory that I’ve missed from choosing Creative Writing rather than Jewish Studies—a class with the wonderful Marilyn Kallet led me to Hana Wirth-Nesher, and I’ll never be the same. Many of these women come from non-academic families and have taught me how to navigate the sometimes-wonderful, sometimes-infuriating culture of academia. Outside of academia, I think of Beth (and before her, Lenny) who works the night shift at the motel—I wouldn’t be surprised if she literally holds the world together while I sleep.

Allison Pitinii Davis interviews Ryan Walsh

APD: “Ghost Factory” begins Reckonings’s documentation of DuPont’s exploitation of West Virginia. The poem starts “It is imprinted on me, the factory on the hill / (no more factory, no more hill)” before tracing the exploitation elsewhere: “Somewhere someone else / will do this for even less.” What do you strive for when reconstructing place, especially a place that has faced such adversity? What concerns drive your process?

RW: With the particular poem you reference and a few more in the collection that explore the zinc smelter plant in Spelter, West Virginia, I think I’m just trying to revisit this place where I was born and where so much of my family’s story resides. I’m trying to do my own reckoning, to recall the place and the complex forces that shaped it, gave it life, threatened it, and keep it limping along. Even the most exploited places on earth—smoldering ruins in war zones, the void of mountaintop removal mining sites—are populated with stories, human and non-human. We should listen to them. Unfortunately, such places are all too common because of our extractive and exploitative economy. But we shouldn’t accept this as normal. I can’t tell you how encouraged I was when I learned that a small group of residents in Spelter had the resiliency and organized will to take on DuPont and sue them and win. I learned about all that after the court case was over and I received notice of the medical monitoring program. That notice in the mail sent me back home to better understand it. Reconstructing a place through language is a bit like reconstructing a dream. You can’t convey it exactly as it was, but maybe you can help someone else feel its atmosphere. There’s a line in one of Charles Wright’s poems from his book Appalachia that speaks to this: “Remembered landscapes are left in me / The way a bee leaves its sting / hopelessly, passion-placed, / Untranslatable language.”

I’m concerned with returning to a place and also feeling its sting. I’m concerned with not swerving into sentimentality while being genuine and of not being too detached when addressing real harms done to people and the planet. I think it’s too easy to see a post-industrial place like Spelter in simplified terms. Either to get nostalgic about the work that once took place there (never mind its dangers) or to see the company as the villain and the workers and residents as victims. Really it’s much more complicated. The town of Spelter existed because of the work in the plant. It was the sole economic engine in town and attracted immigrants, which made for a rich cultural community. It sustained my family for a little over a generation. There was dignity in the work, yet DuPont violated that when they risked the health of their own workers and everyone living in the proximity. The smelter exposed generations of us to heavy metals, yet the men who dumped the waste on the slag heap lived down the street and grew tomatoes in their gardens.

In terms of craft, I often try to consider how a poem can be a kind of inquiry, and I’ve always been fond of Frost’s notion of the “sound of sense,” particularly in narrative poems. Mostly, I’m concerned with making sure my writing stands for what I think of as life-giving things. How can we make sure that our destructive powers are held in check and outdone by our creative powers? How can we bring care and transformation into a poem? We are, as a species, so separate from everything else that is alive on this planet, which is vastly more than us and has existed so much longer than we have. As a result, we’re lonely creatures. I want to find a way to make art that attempts to alleviate that alienation and build connections. I’m concerned with how to engage in the difficult and even frightening work of bringing about transformation and tenderness in our writing and in our lives.

APD: When I write poems about laborers in my community, the last thing that I want them to think is “What the hell is she talking about?” In result, I often err on the side of narrative clarity when the subject isn’t myself—the aesthetic choice is driven by ethical concerns. Many of your poems about labor are also narrative and conversational. I’ve heard writers accuse narrative poetry of being “accessible,” which has become a dirty word in some academic poetry circles. What is the relationship between your aesthetics and your ethics of representation? Do you have thoughts about negotiating class and the academic poetry community?

RW: I didn’t realize that idea about narrative poetry was still a thing, but it seems to me to grow from a false dichotomy about art and labor. Frankly, I try to stay out of circles that think of accessibility (or readability) as an obstacle to poetry. Nearly all of the poets I love and admire, including those who are tenured faculty, are rooted in their communities and are concerned with connecting to readers. I believe people need poetry and poetry needs people, so we have to be willing to share our work with children and gardeners, people who are incarcerated, senior citizens, folks at the VFW hall, as well as with MFA students and professional writers. I don’t consider myself part of an academic community, but I am the lucky member of a tribe of dedicated writers and good humans—some of whom happen to teach in colleges and universities, others of whom work with their hands all day, all of whom are curious about the world around us.

I might be missing the point of your question, but with the poems that focus on Spelter, I made use of some Virgilian guides, drawing on my family members’ own words and experiences in gathering material. Years ago, I had the opportunity to interview Bob Arnold—poet, stonemason, and editor/publisher of Longhouse. He said something along the lines that if you’re going to write a poem about felling or planting a tree, you’ve got to give the reader the whole living tree, roots to crown. You can have all the right terminology on paper, but for it to be a real poem, the tree has to breathe and dance in the wind. To do that, you don’t show the poem to another poet. You share it with a woodcutter or a forester, someone who spends their lives among trees. That resonated with me, but it wasn’t until I was writing these smelter poems that I really employed his advice. Most of my knowledge about what Spelter was like when the plant was in operation (before I was born), came from the stories I grew up with, as well as from interviews with my Uncle Tom, who was raised in the shadow of the plant and worked there under his father (my Grandpa John) one summer while on college break. I shared drafts of all these zinc poems with him along the way, which is quite different than my usual process of sending drafts out to a handful of writer friends who are invaluable readers.

APD: “In the Frame of Innings, Pendleton County, WV” evokes James Wright, and the erasure “Expert Testimony (Perrine v. DuPont, 2008)” is in the powerful tradition of Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead. I also think of Rebecca Gayle Howell and Matthew Neill Null. You’ve cited David Budbill and Galway Kinnell as inspirations. How does your book relate to the larger tradition of Appalachian literature? What does Budbill’s and Kinnell’s work mean to you? I’m especially interested in how they might have inspired you to choose poetry to tell this account rather than another genre.

RW: That’s very kind of you to say, as these are all writers I very much admire. I can only hope that Reckonings might add some little something to the literature of Appalachia. I remember in college discovering writers such as James Still, Irene McKinney, Jim Wayne Miller, Charles Wright, Robert Morgan, and Maggie Anderson—who were writing beautiful poems about the ridges and valleys they knew. It was like they were speaking directly to me. It was inspiring and empowering to see that I could write about the place I was from.

Since college, I’ve been drawn to sense of place and regional identities and even had the great pleasure of editing a literary journal called Rivendell for several years with my good friend Sebastian Matthews. Rivendell had a mission to celebrate the places out of which art and literature are made and enjoyed: geographic locations, communities, and shared sensibilities with each issue focused on gathering writers from a particular place. Our last issue was a return home to southern Appalachia (we were based in Asheville, NC). My sensibilities of other places grew through years of exploring how to define “New England,” while teaching literature and creative writing for many years in the University of Michigan’s New England Literature Program (NELP), a kind of satellite campus and experiment in higher education up in the Maine woods (now New Hampshire).

Like so many others, my story of Appalachia is defined by migrations, by not-being in the mountains, by elsewhere. I’ve lived outside of it for as long as I ever lived within its imagined borders. And now all these years later I’ve landed in Pittsburgh, just a couple hours from my family in West Virginia. The physical and figurative landscapes of the southern mountains have always called me home. Leaving Appalachia and the ineluctable returning (through imaginative and physical travel) has been a shaping influence in my own life, and it has in powerful ways formed the literature of the region.

For many years, I lived in the mountains of northern Vermont. David Budbill and Galway Kinnell, along with the writings of Hayden Carruth, were instrumental in orienting me to life there. I think of their collected works as my pole stars and true north. David was a friend. We stacked wood, cleaned the spring, walked in his woods, listened to jazz records, had tea, and talked poems. His early book, Judevine, is a wonderful collection of characters from his small town, which grew naturally into a successful play. I never set out to document Spelter in such a thorough a way, but if I ever tried, Judevine would be the gold standard to aim for. Galway Kinnell’s poetry is probably the most influential on me in terms of my love of language and willingness to dwell in the wild dark parts of myself. Carruth’s range from lyric to narrative poetry and everything in between is a lifelong education for me. All three of them had fierce love and respect for people, especially working-class people, and for non-human life. They knew how to sacralize life through language, and I am forever grateful.

APD: “The Cloud,” “The Night We Didn’t See,” and “The Pines” negotiate outer space, technology, and ecology. In this collection where humans cause irreparable destruction to each other and the earth, the line “Is your memory backed up?” is a powerful statement about who remembers what, why, and how. In Reckonings, how does poetry function as a tool of commemoration, and what are its limits? What do you want contemporary readers to understand (or stop misunderstanding) about West Virginia after reading?

RW: West Virginia is a place to break your heart—both with its wild beauty and its degradations. I believe there’s importance and dignity in bearing witness. Like so many other places in economic stress, it was a kind of sign of success to get away, to distance yourself from your home. I internalized that unspoken message and left West Virginia when I turned 18. I haven’t lived there since, but I’ve also never stopped looking back.

At the risk of sounding speculative or dystopian, with poems like “The Cloud” and “The Pines,” and the poems I’ve been writing recently, I’m trying to imagine what life might be like after our current systems of civilization decline or collapse or are sloughed off for something better. And I think about how people in parts of Appalachia and so much of the southern hemisphere are already living through it with climate catastrophes, war, and the ravages of capitalism. I think about the monks who hunkered in the Irish cliffs after the fall of Rome, copying manuscripts that would outlast the Dark Ages. Just like looking to the heavens for guidance, turning to poetry and story have been around as long as humans. But commemoration has its limits, so how do we dream forward a world that transforms our current systems but isn’t merely fantasy or dystopia? How do we imagine through literary art a better world that we can truly inhabit?