Russell Persson’s THE WAY OF FLORIDA Reviewed in The Wall Street Journal

/in Uncategorized /by Christine Kelly

Sam Sacks reviewed The Way of Florida in the May 30, 2025, edition of The Wall Street Journal.

Am I Even a Bee? Author and Illustrator Visit South Lake Tahoe First Graders

/in Uncategorized /by Christine KellyNotes on The King’s Highway

/in Uncategorized /by admin

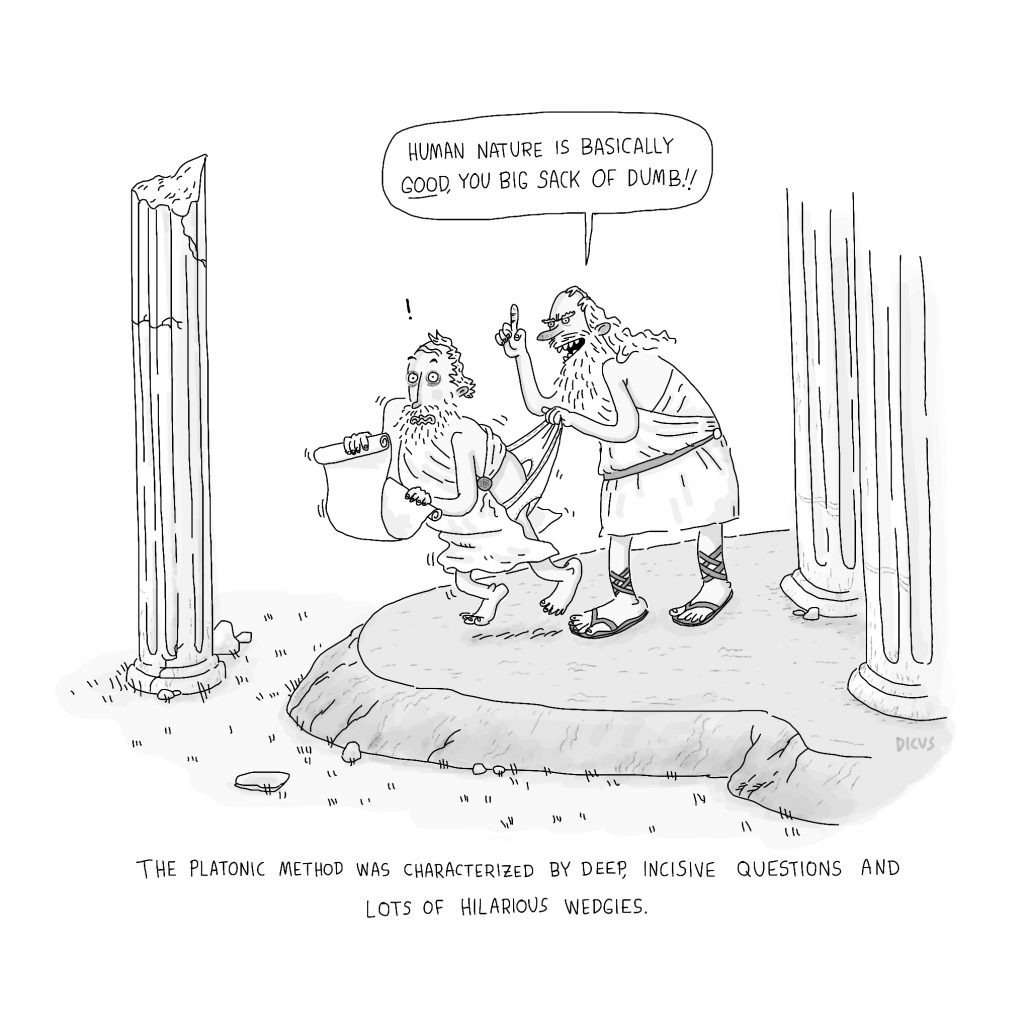

There’s an old philosophical question that goes something like this: are people basically bad with a few good tendencies, or basically good with a few bad tendencies?

The King’s Highway is one small episode in one person’s years-long attempt to answer that question.

On the one hand, it’s not difficult to find uplifting stories in the news of selfless people rescuing people stuck in tubes, extracting babies from tubes, or opening peoples’ clogged airways with small tubes. (Apparently I can only think of tube-based emergencies just now.)

On the other hand, and I swear this is a true story, I once saw a woman literally poop onto a car because it was double parked and she couldn’t get out.

Now, ask yourself. Do those seem like the actions of someone who’s basically good? Do you detect even the faintest blush of basic goodness issuing forth from betwixt those two pink cheeks?

As a cartoonist, this enduring philosophical question poses two interrelated problems, one of substance and one of craft.

To wit, on the one hand, there are only so many tube-to-human encounters I wish to draw. On the other, no one wants to read a book full of (figurative, of course) car-poopery.

To put it slightly less grossly, it’s hard to write about humanity, its basic goodness or basic badness, and still be funny.

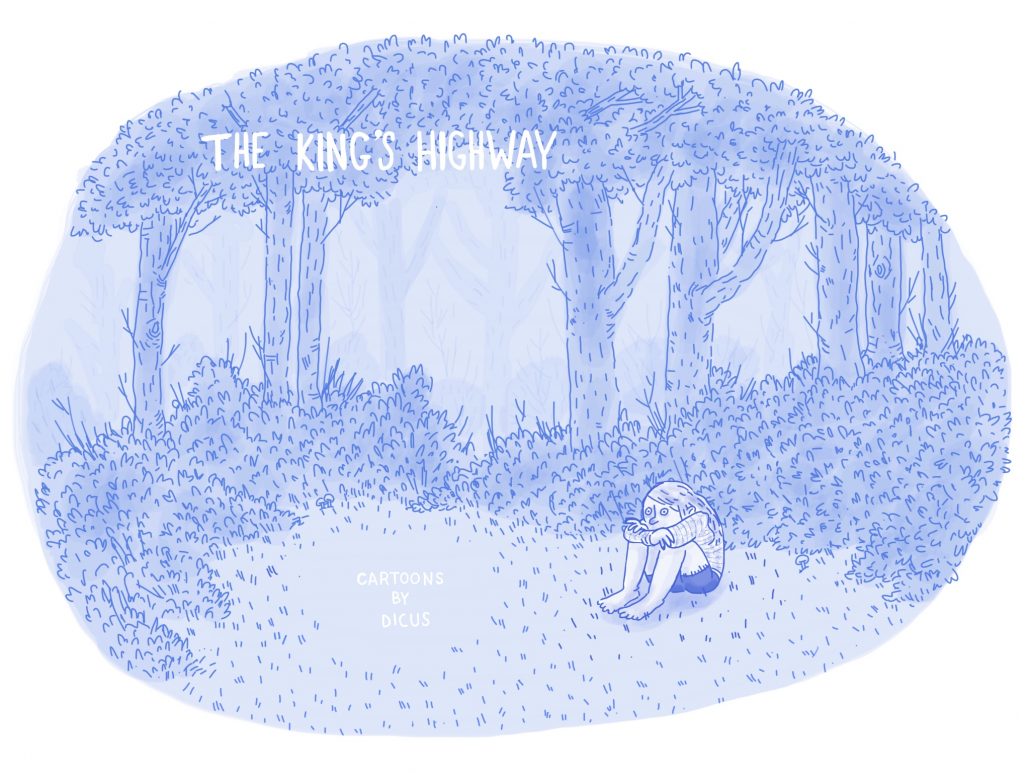

To show my cards somewhat, I’m not a very optimistic person, and it has been pointed out to me more than a few times that I have a slightly dark sense of humor. While some purveyors of comedy thrive in the dark side, it is risky territory, and anyone trying to strike the right balance between laugh-aloud satire and thought-provoking commentary might easily find himself or herself sinking into the numb, existential despair of a French pubescent in a silent film. Here, for example, is an actual rejected cover design for The King’s Highway.

The kind editors at Baobab Press, seeing this cover design, sat me down and calmly explained, the way one might explain to a geriatric monkey that buttons aren’t candy, that making people sad isn’t going to make them want to read a book of cartoons.

Taking their feedback to heart, I gave it another pass:

Clearly, some part of me thought that I could slap some clown colors on this Prozac ad and it would magically become funny. Obviously, not so. Back to the drawing board, to try to balance dark social satire with light-hearted laughs.

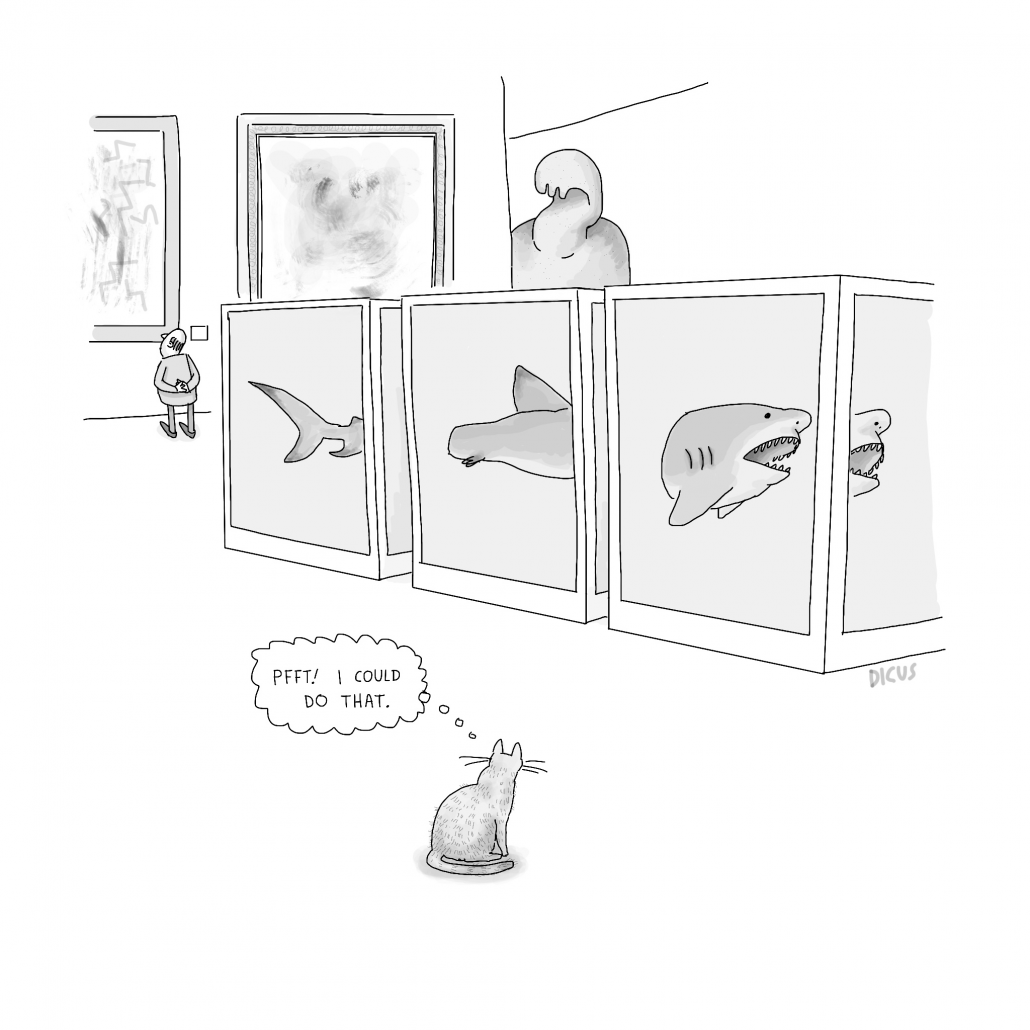

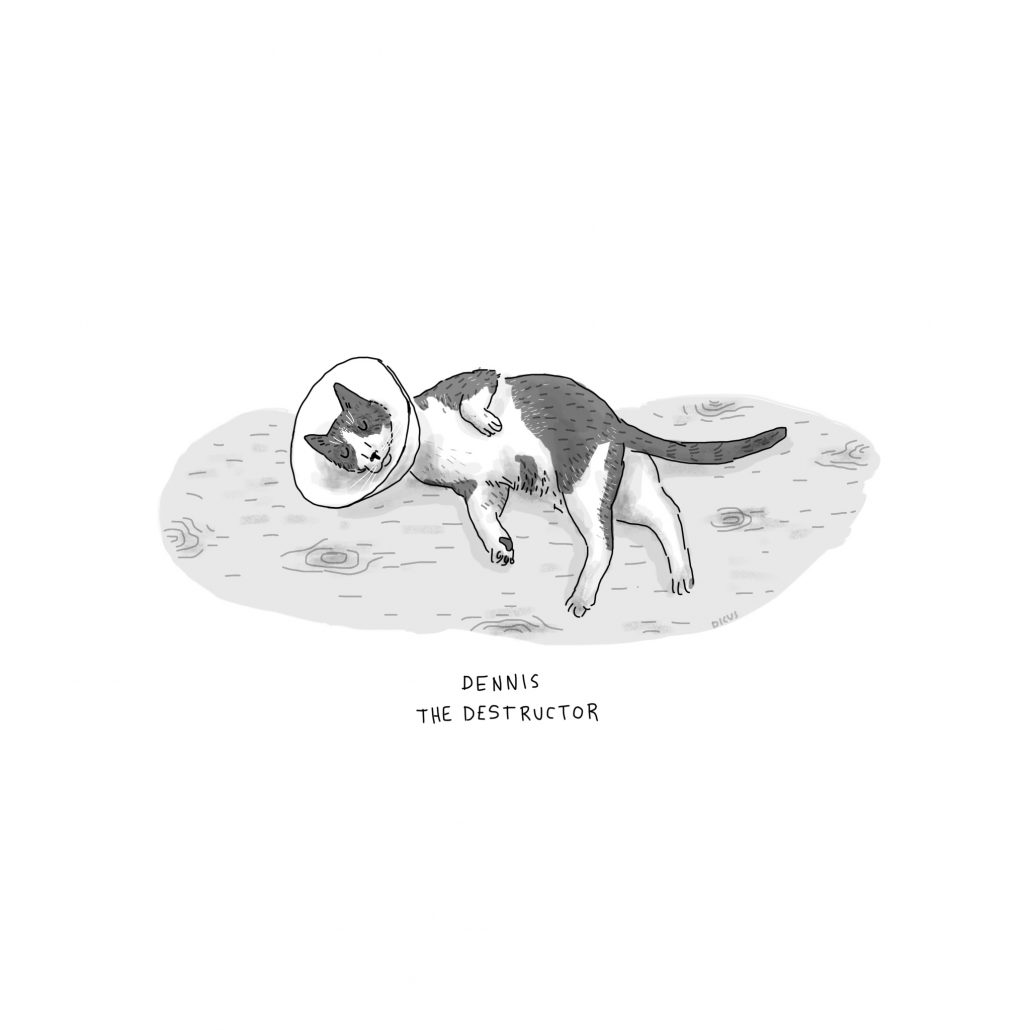

In some ways, as it turns out, I was looking too hard. The answer was, in fact, right in front of me the whole time. Specifically, a few inches in front of my face, licking itself and sneezing onto my sandwich. It was my cat, Dennis (who also, by the way, thinks he’s a dog).

Dennis is a cranky bastard who can yawn his rotten breath directly into your face, make you bleed profusely, dissect your brand new coat, and then immediately afterwards, somehow, make you belly-laugh. He has excellent comic timing, for one thing. Once, while looking particularly sweet, and while my wife and I were having a grave and hushed conversation about some of his many and serious health problems, my wife looked at him affectionately and let him know that he was loved. In response, he leaned close to her, his big eyes glistening, and he slapped her with two hands. Do you know how difficult it is for a cat to slap you with both forepaws? It takes a lot of effort and balance. A cat really needs a solid core to pull off a good two-hander. More importantly, a cat needs a comic style that is somehow both mean and hilarious in equal measure.

To take another example, framed pictures enrage Dennis. He has a fierce and irrational hatred of them.

If Dennis sees a new framed picture on the wall, he will cease all activity and become consumed with bloodlust. He will pause mid-stride, glare at it for a few pregnant moments, slowly boil with rage, and then, when it fails to retreat at the very sight of his mighty fury, he will dart across the room and hurl himself against the wall, claws-first, with what passes in cat-world for Spartan, self-sacrificing fortitude. He will then spend the next few years scratching at the wall in its vicinity, looking at it the way I might look at a burrito full of hairs. It’s more than a little destructive, yes, but it’s also super funny. And he knows it.

Everything Dennis does is either destructive or hilarious – mostly, it’s some mixture of both. Actually, just a look will do, usually: the vacant, blinking stare of an animal who just doesn’t comprehend what a couch is, what it means to buy one, why it ought not to be turned inside-out, and why the two red-faced bipeds that live with him are jabbering at him in shrill, elevated voices.

More to the point, Dennis has the at-times salty attitude of a human cartoonist trying to keep a sense of humor in a world full of people who are either tragically stuck in tubes or editorially pooping onto others’ cars.

In short, Dennis is a master of craft. He finds ways – however exaggerated and bizarre — to express his feelings about a world that he doesn’t understand and sometimes doesn’t like, but without being cruel or fatalistic. For all of his comic violence, Dennis knows he isn’t hurting anything, not really. He carries himself with a puckish glee that shows his destruction is always half-play, and more than a little fun.

So does Dennis think the world is basically good? Basically bad? Where does ol’ Dennis Sandwich Sneezer sit on the human nature debate? I suspect he has strong thoughts on the subject, actually. He may know better than me, in fact: there’s a kind of wisdom in cats (who think they’re dogs) who indulge in boiling rage in the most comical ways, only then to surrender to the simple pleasures of a patch of sunshine.

But he’s not telling. And that’s perhaps his most important lesson. Dennis lets us make up our own minds about how odious framed pictures are. And while he’s been generally successful in getting me to enjoy sunny days a little more, to make time for boxes once in a while, and to developing innovative ways of letting squirrels know that our fire escape is very much not their toilet, his greatest achievement, as far as I’m concerned, is getting me to notice ordinary, mundane things I normally wouldn’t — and to think about what those things, and my reactions to them, might say about a complex world and my feelings about it.

And, in my view, that’s exactly what good cartoons should do.

An Interview with Douglas W. Milliken

/in Uncategorized /by adminAuthor Douglas W. Milliken, who contributed his story “Thirteenth Apostle’s Star” to Baobab Press’s This Side of the Divide: Stories of the American West, discusses craft, beginnings, and living as a professional writer. “Thirteenth Apostle’s Star” along with several other excellent stories appear in Douglas’s second book, The Blue of the World, from Tailwinds Press. His first book, To Sleep as Animals, was published by Publication Studio/PS Hudson.

Milliken’s stories demonstrate an impeccable eye for the slightly askew and uncanny in and of images, objects, and people. Written in accessible yet exultant prose these stories are studies in rendering emotion through detail and tone. This work is an immersive experience, startlingly subtle, deftly-crafted .

Baobab Press: Douglas, your connection with landscape is apparent, so much that it becomes a character. How did you land on this approach to fiction? Do you think this approach lends itself to the beauty of your prose?

Douglas W. Milliken: I grew up in a very remote part of northern Maine, in the last house on a dead-end road far from the nearest town, so a lot of my time was spent solo, usually wandering around in the woods and fallow pastures behind the house or reading in the cemetery down the road. In a sense, that spread of acreage was my most consistent companion. There was a ghostliness to the overgrowth and wind and rolling shoulders of the ground underfoot. Somehow, in all that abounding solitude, that ghostliness made me feel less alone.

When I was eleven or twelve, I finally got glasses (despite having lobbied for and known I needed them for years) and I remember, driving home with my mom from the optometrist wearing my big chunky coke-bottles for the first time, realizing that I could actually see the individual leaves on the trees, that the vibrant world surrounding wasn’t just a green blur below a blue blur but in fact was dizzying with richness. I’d become so used to my near blindness that I’d forgotten how the world persisted in detail when it was beyond arm’s reach. It was such a rush of way too much. My life up to that point revolved around spending time out in the woods, yet with the pedestrian suddenness of slipping on a pair of glasses, I was confronted with the dropkick epiphany of just how much I’d been missing.

BP: To Sleep as Animals takes place in Nevada. Did you find it difficult to write about this landscape?

DWM: Not at all. The summer I spent in Reno was the first time I’d ever really been outside the Northeast, and while it was immediately evident how extreme the landscape was (I mean, even the thistles were next level), it was equally evident how teeming and varied the place was and how nearly none of that resembled the world from which I’d come. I really couldn’t help but fall in love with it, memorize it as best I could. I hope I’ve done it justice in my writing.

BP: Many of your stories are akin to legends or tales through their otherworldliness. What effect do you want this dream quality to have on the reader? Why present the world this way?

DWM: I think people are a lot more accepting of unlikely phenomena than the movies suggest. I’ve never known anyone to go running and screaming down the street because they think their house is haunted. But I know a ton of people who very casually believe ghosts are responsible for things they can’t explain (or angels or demons or whatever). Because the brain is always trying to make sense of the sensory input it receives: it wants there to be a cogent whole to what we experience. So we adapt to the weirdness, incorporate it into our understanding of reality (or we deny it: denial is wicked popular). In that sense, a minor hallucination of a muppet in the kitchen actually sits quite comfortably next to the flies circling the ceiling fan or the bottle of Cholula on the table.

All that said, I have variously and purposefully throughout my life entered into that same general strangeness, primarily through sleep deprivation or interrupting my sleep cycle with the explicit intention of altering my conscious state. It was in fact the entire spring before flying out to Reno that I dove deep into personal sleep disturbance, waking myself from REM sleep three or four times in the few hours I allowed myself to rest, all in order to keep a dream journal for a class. I’ve also (less fun, less purposeful) been lead-poisoned as an adult, which turns out to have very similar psychological results (I’m amazed I can coherently string together even the simplest sentence). But regardless of how I got there, that waking-dream reality is something I’ve very much experienced, so I guess it stands to reason I would write about it with an air of casual plausibility.

Whether my characters are working through something surreal or banal, though, my end goal is the same: to depict as accurately and honestly as possible what it feels like to be this person, living this life, surviving these things. So if the character is unalarmed by and accepting of the muppet in the kitchen, man, who am I to say that’s weird? The scene’s got to be described with equivalent acceptance and calm.

BP: What did you read when you became a reader? When you were getting into writing? Is it dramatically different from what you read now?

DWM: The first book I read on my own was about seven (apparently identical) brothers who each had a special invulnerability. One could not be smothered, another could not drown, another could not be hanged, and so on down the line. The story begins with one brother being wrongfully accused of murder (he should actually have been tried for manslaughter) and sentenced to death by hanging, but on the day of the execution, the brother who can’t be hanged stands in for the original and, of course, survives. So then it’s execution by fire or by smothering or whatever, and with each attempted execution, a different brother stands in to save the life of the original criminal brother. I can’t remember how the story ends except that none of the brothers die (I guess the townspeople got tired and gave up). But I think it’s telling that, at four years old, I was already drawn to stories about death, punishment, and identity.

I was in 6th grade, though, when writing became a concrete and conscious act. Throughout my childhood I was writing stories or constructing narratives around my drawings of demons and monsters or whatever, but it wasn’t until Mrs. Thurston started assigning writing projects—like really encouraging us to come up with our own stories—that I first recognized the joy I found in storytelling. At the time, I was reading Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s fantasy cycles, Timothy Zahn’s Star Wars novels, and a ton of Stephen King—although Carlos Casteneda and The Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda were somehow also part of the mix—so those early stories bounced around a lot between the grotesque and the mystical, space operas and psychedelic psychopaths and that sort of thing.

Which, to an extent, I really do miss (the stuff I read, I mean, not the stuff I wrote). I still enjoy the genres, but have found way more enjoyment recently in watching those stories as opposed to reading them (few things are as comforting as the warm familiarity of Captain Picard’s command to make it so). Now and then I’ll attempt writing within a genre, but the resultant stories are always perversions far afield of classic sci-fi or horror. Which is fine: I don’t think I’d find much joy in writing a by-the-books fantasy novel (although it’d be dope to just once, with authority and just cause, have a dragon appear in a story). As much fun as that stuff is, I love the work I’m making now, informed as much by Joan Didion and Denis Johnson as Hanne Darboven and Busdriver. If writing the weird existential nightmares I write means I have to spend more of my time reading Werner Herzog describing Werner Herzog, it’s a price I’m willing to pay.

BP: When/where do you think you started to write in earnest/ became a writer?

DWM: There’s not really a single ah-ha moment so much as many notices and reminders that this is what I love and I’m capable of doing it better. Mrs. Thurston’s language arts class, as I mentioned, made me aware of the satisfaction of rendering a vivid, textual world. My semester-long experiment in sleep deprivation coincided neatly with a tremendous surge in productivity, but that could just as easily (and perhaps more rightly) be attributed to finally having a community of supportive, driven artists to engage with: it’s when I found friends who were actively doing art that I stopped talking about being a writer and really started to work. The time I spent immersed in the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies’ writing program definitely marked a new level of dedication, as did the winter after my mother died when—with nothing else to do but grieve and get lonely—I drafted To Sleep as Animals in six breathless weeks. And so on. It’s like leveling-up in a video game. I reach a certain aptitude in my work and practice, then an event comes along that tells me, “you could be doing this harder, you know.” Each of those events is when I become a writer again.

BP: What do you do for a living and how does this vocation align with, help, and/or hinder your goals as a writer? What are your goals as a writer and for your writing?

DWM: After having spent most of my twenties wrecking my body in one trade or another, I’ve finally cobbled together a system wherein I work the apple harvest each fall, pick up freelance editorial gigs here and there throughout the year, and spend the rest of my time writing and engaging in all the consequent business of being a professional writer (which is to say, sending out countless emails and every now and then getting high off giving a reading). So obviously some years are better than others, but between having inexpensive vices, a small amount of money saved or inherited, and a partner who is okay with (and better at) being the breadwinner, everything somehow remains above water. At least for the time being.

Working the apple harvest kinda began as a stop-gap between other seasonal jobs and attending artist residencies. But after my first season in the orchard, I started selling stories and traveling to give readings more consistently, so the harvest became an opportunity to give myself a few months’ break from being a writer and let someone else be the boss, allow my mind to wander while my body did the work. But I’m not sure that’s how it’s really worked out. Some years, fall is when I have the most opportunity to give readings or when a new chapbook is published. Sometimes the apple harvest is slim, which means I end the season with less cash than I’d hoped. And sometimes winter arrives and I feel totally disconnected from the work I’d been doing earlier that summer. But I love being in the orchard—by the time October gets crisp, there’s nowhere else I’d rather be—so I guess it’s worth it. (I think it’s worth noting that all the stories in the collection that somehow involve apples—like “Saltwater Baldwin” or “Blue of the World”—were written before I began working in orchards.)

As far as goals, man, I just want to have my stories read and not have to work for some [expletive deleted]. I’m very aware that what I do is not for everybody, but when a piece clicks with someone and they share that with me, their reaction is affirmation enough to keep doing whatever it is I’m doing. In another time or place, maybe I’d have been a rabbi or a shaman or whatever other vocation there is whose aim is to reach toward the ineffable and in the process connect with another human, share in that ineffability. Although maybe that’s just communication, what any one of us are attempting at any given moment. Just struggling to connect with another human being. No wonder it’s such lonely work.

An Interview with Dorene O’Brien

/in Blog Post /by adminDorene O’Brien is a Detroit-based writer and teacher whose stories have won the Red Rock Review Mark Twain Award for Short Fiction, the Chicago Tribune Nelson Algren Award, the New Millennium Writings Fiction Prize, and the Wind Fiction Prize. Baobab Press is honored to publish her latest short story collection this February, What It Might Feel Like to Hope, which considers the infinitely powerful, and equally naïve and damning force that is human hope. We recently asked Dorene to share a behind-the-scenes look at her writing process, inspiration, and creative horizons.

Baobab Press: Many of the characters in this collection grapple with depression, anxiety, and feelings of isolation. But despite their darkness, these stories are deeply funny. How do you tend to think about the ways that humor and darkness work together in your fiction?

Dorene O’Brien: I think my stories reflect life in all of its darkness and absurdity. My grandmother used to say that when offered a shit sandwich you either laugh or cry, and she chose to laugh. My characters are offered lots of shit sandwiches but, like we all do, they often use humor to cope with the latest event that threatens to break them. I don’t set out to write humorous stories (except for “Eight Blind Dates Later,” which I knew would be a comedy as whenever your mother sets you up on eight blind dates you must laugh through the tears). But bleakness and gravity should be balanced with humor not only to keep readers tuned in to a tough message but to keep them entertained.

BP: What draws you to the short-story form? What do you think it can accomplish that the novel perhaps can’t?

DO: When I was a younger and more impatient writer the short story was something I could “finish” and feel that sense of accomplishment before moving on to the next one to feel it once more. Now I am interested in the form as a challenge in brevity, which demands authors create entire worlds and character histories in a very small space. We must use just the right words while also withholding just the right information so that readers are seduced into colluding with us to make meaning. If the “white space” is as charged with clues as the words printed on the page, the story will emerge in a way that is more gratifying to readers, who have used their insights and perceptions to help craft the tale. There is simply no room in stories for devices used frequently in novels, such as lengthy digressions, false leads, casts of thousands.

BP: Who are some of your most important literary influences?

DO: The first “great novel” I read was Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and it broke open my mind. I was stunned by Twain’s ability to juggle so many literary balls simultaneously: weaving a rich, authentic setting that encapsulated the tumultuous racial history of the country, drawing captivating, sympathetic characters through dialect and arresting backstories, and delivering a confrontational message about a subject that tore the country apart using humor. Twain taught me that fiction more effectively influences people than most other forms. Winning the Mark Twain Award for Short Fiction many years later remains one of my most gratifying achievements. Joyce Carol Oates was an early influence because she is fearless in her style, content and delivery. That is, nothing is taboo; if it happens in life, it can happen in fiction, which is of course a reflection of reality. Andrea Barrett, who was trained as a scientist, was also an early influence who showed me that getting your geek on in fiction is acceptable. I would not likely have written “The Turn of the Wind,” a story seated in crystallography, had I not read her Ship Fever story collection.

BP: When did you know you wanted to be a writer? Was there a point in your life when you decided to take your craft seriously?

DO: I started writing—and reading—when I was very young as an escapist activity. My childhood was not an easy one (ask any writer and they will more often than not have grown up in difficult circumstances), so reading about worlds that were like mine made me feel less alone and reading about worlds that were much better gave me hope for something more. But creating my own plots and settings allowed me a form of control I never felt at home, and this was a salvation of sorts. Over the years I collected many notebooks with stories and poems, but this was more therapy than writing. I knew I wanted to be a writer but was afraid to chase that dream as it was the only one I had and if I failed what else was there? In fact, I even majored in journalism so that I could land a “real” job, and when I applied for graduation my advisor said that I had taken so many creative writing classes I was only two away from a second major in English. So I stayed on to double major and continued to write stories without telling anyone, submitting them to small literary journals. I was taking my craft very seriously then, reading and writing voraciously, developing the acumen to determine the difference between a successful and a mediocre story. Slowly the acceptances rolled in, building my confidence to enter contests, which I slowly started to win. I still don’t call myself a writer, a title I’m not sure I’ve yet earned. The apprenticeship is long, and I am still growing and learning.

BP: What are you reading / watching / listening to right now?

DO: I just finished reading Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere, Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing, and Kate Moore’s Radium Girls. I am watching Black Mirror, the Great British Baking Show and Vikings (I have a Vikings obsession. I once tried to write a serious historical fiction story about the final Viking voyage but the characters took over and turned it into a comedy). I typically listen to classic rock and jazz. I go back to old favorites—Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Talking Heads, Elvis Costello—but I also like Radiohead, the Beastie Boys and the Arctic Monkeys.

BP: What’s your writing process like?

DO: I tend to work on two projects simultaneously, staying with one until I hit a wall and then turning to the other; I have fallen into the trap of not writing at all until I had a breakthrough with a stalled work and that is no way to be a writer. I am currently finishing a novel and, while writing it, I finished another story collection! I am more energetic in the evening, so my writing hours are late, though I have started writing during the day as well, something I forced myself to do during a writing residency at the Vermont Studio Center. I am also interested in many disparate things and so I write about them rather than writing to current trends or contest themes.

BP: Where do you turn for creative inspiration?

DO: Books, because reading riveting literature motivates and teaches me. And my fishbowl. Whenever I have an idea for a story when I’m out and about, I jot it down on scrap paper before the concept flees my ever-filling brain. When I get home, I throw the paper into my fishbowl, which is now about half full (and does not contain fish!). When I need a new story I idea I reach in and grab a paper and am immediately taken back to the moment of the idea’s inception, that original spark reanimating me. Where I do not seek inspiration is from people who tell me that they have a great story idea I should write. Most often their vision is unique to them and only they can relay it. Imagine being responsible for someone else’s brilliant plan! It’s like trying to raise their child as they look over your shoulder.

BP: You also teach creative writing. What are some of the most important things you want to impart on your students, and how has teaching this craft impacted your own work?

DO: Be patient with your ideas, investing the time and effort they need to grow and thrive. New writers have a surplus of concepts so that when one does not flow effortlessly into a story, they ditch it and move on to the next. I encourage them to consider the work required to mold a nebulous thought into a world replete with characters, setting, conflict and resolution that must work together to deliver a message and a full experience to readers. I also encourage them to be kinder to themselves, to quit beating themselves up when the work on the page does not look like the narrative they had envisioned. Thinking and writing are very different things—thoughts arc and snap in our heads, often concurrently, whereas every story is linear, delivered one word at a time. I tell them that I would be shocked if the mental plan and story were the same because evolution occurs naturally in the creation and that this is a good and necessary thing.

My students inspire me every day, so teaching creative writing has augmented my skill and my investment in my own writing.

BP: You identify as a Detroit-based writer. Can you talk about the ways this city has shaped your work and your voice? Do you think it’s important for writers to have a strong connection to place?

DO: My writing, particularly my first story collection, is gritty and was definitely inspired by my experiences in and knowledge of Detroit. “Way Past Taggin’” is about a graffiti artist living and tagging in the city, and it’s a story I could never have written if I lived elsewhere. “Honesty above All Else,” which is in the forthcoming collection, is set in Corktown in Detroit and was inspired by my visits to O’Leary’s Tea Room there before it closed in the 90s. But the story also pays homage to many metropolitan landmarks: Cobo Hall, Tiger Stadium, The Fisher Building, the UA Theater Building, Hudson’s, the Seven Sisters, etc.

I actually don’t think writers need a strong connection to place as it’s our job to imagine landscapes and settings, but I do think place is important in fiction as every story is set somewhere! Even if location is less important than, say, conflict or characterization in a story, readers will be distracted if the smallest allusions to setting feel wrong.

BP: Can you tell us a little bit about what you’re working on now?

DO: I just finished a story collection called A Coterie of Uncommon Women and I am working on the second draft of a hybrid literary/sci-fi novel. Following that will be a story collection focusing on natural and historical oddities, such as the Loch Ness Monster and the Great Red Spot above Jupiter.

Craft Talk: Poets Allison Pitinii Davis and Ryan Walsh

/in Blog Post /by adminBaobab Press’s new literary imprint, Red Ochre, is devoted to elevating voices that rescript our conceptions of identity and place. The imprint launched with Allison Pitinii Davis’s 2017 poetry collection, Line Study of a Motel Clerk, a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award’s Berru Award for Poetry and the Ohioana Book Award. The collection examines a family’s century-long effort to make a home in a changing world, with all the grit, beauty and truth of the working-class immigrant struggle. This February, we’ll release Reckonings, the debut poetry collection by Ryan Walsh that interrogates the dissolution of American industry and rural community.

Since these collections share interesting thematic intersections, we recently asked Pitinii Davis and Walsh to sit down for a craft talk. They asked each other about place-specific poetry, about artistic inspiration, about the ethical implications surrounding their work, about the capacious power of poetry, and much more.

An Interview with Bernard Schopen

/in Blog Post /by adminBernard Schopen’s latest work, The Last Centurion, is a gripping, perceptive account of a misfit struggling to hold fast to ancient values of loyalty and duty in a world where little is as it seems and only the past can be trusted. The author recently shared some insight with us about the novel’s thematic ambitions and what readers can expect from his next project.

Baobab Press: The novel’s main character, Tad, is fixated on Marcus Aurelius. Can you talk about how Aurelius made his way into the novel and what drew you to write about this historical figure?

Bernard Schopen: Tad is an odd, even strange young man. Since boyhood he has admired the Romans, their achievements and discipline, and, although wounds have taken him from the battlefield, he understands himself to be, still, a soldier. Martial values like duty and honor and loyalty give meaning to his life, the stern consolations of stoicism appeal to him. Meditations, by the Warrior-Emperor Marcus Aurelius, is a sort of sacred text for Tad. He reads it as some read the Bible. The quotations from it reinforce for the reader Tad’s view of himself and the world he finds himself in. My favorite, by the way, is “Soon you will forget everything; soon everything will forget you.”

BP: Where did the inspiration for The Last Centurion come from?

BS: I’m not really sure. I’ve visited England a couple of times, and there’s always an excavation going on somewhere, but I don’t know, specifically, what got this story started. I just found myself imagining a young man at an archeological dig day-dreaming about being a Roman soldier stationed in a wilderness outpost in a foreign land. From there it was muse and manipulate, one thing suggesting another, characters popping up and saying things, images appearing, everything shifting, notions nudging in. This went on even after I started writing. I remember feeling, as I wrote, that I was not so much telling as discovering the story.

BP: Tad is emotionally and physically wounded from his experience in the Afghanistan war. How did you portray his experiences so authentically?

BS: I’d read several accounts, both fiction and memoir, of the experiences of young Americans in Vietnam and home again, as well as a couple of good books on the Afghanistan conflict. Fortunately, I have a good friend, a Vietnam vet, who was able to tell me when I got it about right.

BP: How would you describe some of the underlying themes at play in this novel?

BS: The novel has three basic, related concerns. The most obvious, I suppose, is the issue of empire building past and present, its consequences for cultures as well as for individuals who are victims of or complicit in it. Another is the question of the human impulse to violence. And the third is the difficulty for thoughtful people in finding an acceptable set of values to live by. But while these themes are important, I would stress that The Last Centurion is first and foremost the story of a wounded young American, of his struggle to find an honorable way to live and to love among people who, one by one, betray him. It answers none of the questions it raises. It offers the reader not a lesson but an experience.

BP: Fans of your earlier work (the Jack Ross detective novels and Calamity Jane) have fallen in love with your depictions of the American West. Do you see any correlations between the world you’ve created in The Last Centurion and the territory you’ve explored in your earlier novels in terms of moral concerns, landscapes, scope or themes?

BS: The problem of finding a set of values to live by is, I think, central to all my fiction. My detective, Jack Ross is a man tugged at by dichotomous attitudes, those perhaps over-simplified as liberal and conservative. Calamity Jane relates a direct conflict between these views, in the encounter of Jane and Ione. A similar contest centers this new book. In the earlier novels, I was concerned with the effect of place, of the environment, on people who live in the American desert—thus, the careful descriptions; but in The Last Centurion, while Cambridge and environs get a close look, my interest is not so much in the physical landscape as in the history embedded in it.

BP: Can you describe your writing process for this novel?

BS: It was pretty much the same for all my novels. I think and take a few notes. Then, when I know where I want to start, more-or-less and where I want to end, probably, and how I’m going to get, sort of, from one to the other, I start writing. I revise constantly along the way, so that by the time I get to the final sentence I’ve got something like a coherent whole. Then I revise some more. I might say here that the revision of The Last Centurion was helped significantly by the efforts of Christine Kelley, the publisher of Baobab Press, as well as Wes Reid and Curtis Vickers and, especially, Margaret Dalrymple.

BP: Who are some of your major literary influences?

BS: For the detective novels, Ross Macdonald, obviously. But probably also John Updike, whose “Yes, but” attitude toward moral dilemmas informs my fiction, which is why readers won’t find in it any absolute moral assertions, only questions, problems, and complexities. Other than that, I have been encouraged by and tried to learn from writers who carefully choose the words they use and attend to the way they arrange these words in their sentences.

BP: What’s the last great book you’ve read?

BS: I’m a little uneasy with “great.” Let me name the novels I’ve read or reread recently that I think highly of: Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen; Housekeeping, by Marilynne Robinson; The Remains of the Day, by Kazuo Ishiguro; Felicia’s Journey, by William Trevor; The Spire, by William Golding, and Blood Meridian, by Cormac McCarthy.

BP: What’s next for you? Can you tell us about your next project?

BS: Soon I’ll begin, with the Baobab staff, preparing for publication in 2019 a new Jack Ross detective novel. And I’m polishing a story set in London, which I’ve been working on for years. Beyond that, I muse . . .

An Interview with Roger Arthur Smith

/0 Comments/in Blog Post /by adminRoger Arthur Smith’s captivating debut novel, Echoes, which hits bookshelves in March of 2018, melds the supernatural with 1950s noir. We recently caught up with the author to learn more about the inspiration behind the novel, his writing process, and the real story behind one of literature’s most compelling crows.

Baobab Press: Where did the inspiration for Echoes come from?

Roger Arthur Smith: The story begins with libraries. I love them–and book stores. I had already written a couple of essays about them and wanted to try one about the first library I ever went to on my own. I had some notion of compiling a book-place memoir.

My first library was the Mineral County Library in Hawthorne. I wrote a draft about my visit: gritty desert wind buffeting me on the way there, a pretty young librarian, my clueless wonder, my first library book (Dr. Suess’s One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish), and my pride in getting a library card. It was a personal essay, and when I read it through, it seemed awkward, flat. First-person point of view does not suit me. So I wrote another draft from a disembodied point of view. No good. The problem, I decided, was me, an average little kid. So I wrote a third draft from the point of view of the librarian, and I made the boy not me but a kid who is eerie and slightly unnerving to the librarian, who oversees the small building all alone on the desert’s edge.

That was more interesting. But why is this eldritch boy there? After several tries to answer that, I wrote the prologue about a girl who is kidnapped, abused, and killed. A victim of the worst human depravity. So I added another kid to the mystery, which suggested a sequence, which piqued a fantasy. If only there were more justice in the world than we humans can mete out on our own, something to stop monsters when we fail. A supernatural agency, for instance. A mystery requires an investigator. I introduced Will Dubykky. A supernatural mystery suggested a supernatural investigator, and so I made him one. Then I sent him on his way to figure out what was going on.

BP: Echoes has such a strong sense of place. What’s your relationship with the Nevada desert, and why was it important for this book to take place in this unique setting?

RAS: My family moved from a small town in Montana to Hawthorne in 1958. I was five. Hawthorne was like an outpost in a barrenness that was a shock to my parents, less so to my older sister, who made friends easily, and a wonder to me. It was the first time that I looked at things not just right in front of me or in the middle distance but as far as the horizon. It shaped my idea of landscape: long vistas, hulking mountain ranges, sunlight like an invasion, colors that ran from drab to crazed.

The Great Basin was not like anything I had seen, not even in horse operas: a vast, grooved saucer where not even the rivers escape. Hawthorne was not like other towns. It was almost surrounded by naval ammunition bunkers. Kids at school sometimes bragged (falsely) that they could spot mushroom clouds from the Nevada Test Site. Uranium prospectors hung around. A Korean war veteran sliced up his wife and daughter, who fled across the street to bleed in our living room while my father went to talk him down. In the sheriff’s office a deputy was examining a confiscated rifle when it went off; the bullet traveled across the street and killed a woman in her house. There were no speed limits; single-car crashes were more common than collisions. A minor earthquake. Hunting Easter eggs under a blinding sun on frozen ground. A flash flood that neatly sliced a highway. A dust storm approaching like some Old Testament plague. An prehistoric serpent that was said to lurk in Walker Lake. Going to school with Native Americans and African Americans, the first I ever met. Playing marbles with ball bearings. Catching lizards and horned toads among cast-off ammunition crates. Bouncing over dirt roads, my father driving his ’51 Ford pickup, to ghost towns on the hunt for treasure. Whacking cones out of piñon pines for their nuts.

The list could go on, but the point is that I accepted it all as normal. I’ve lived elsewhere in Nevada–Carlin, Yerington, Carson City, Reno–and those places expanded my view, but I was already primed to regard the state as a place of singular dangers, adventure, dehydrating beauty, mesmerizing distances, uneasy communities, precarious industries, fierce love of sports, contradictory weather, gambling (as well other vices, incomprehensible to a boy), and heedless freedom. I reveled in it.

Now, when a story idea comes, it arises from those circumstances. No other setting suits so well.

BP: What was your writing process like for this novel?

RAS: I wrote Echoes, as my wife’s uncle liked to say, for my own amazement. Definitely an amateur’s indulgence. So–I can’t recall now whether I was more astonished or more pleased–when Christine Kelly called to say that Baobab Press might publish it, I had a job of work before me to make it actually publishable. Many drafts followed, many comments, suggestions, and doubt from others. Whole sections that I had fun writing were ejected, such as a long excursus on the number 4 and another about crow behavior. Chapters did a square dance with each other. Characters’ names changed. Scenes appeared and disappeared until, I believe, the story began to hide from me, scared about what strangeness I might inflict upon it next. But with the steady care of my editors and a measure of useful skepticism from family, the story found a course that did not depend wholly upon my whims.

BP: Can you talk about creating the character of Jurgen the crow? Was he based on a relationship you have with a specific animal?

Although I have kept dogs and cats, I am not innately a pet person. I prefer wild critters, especially birds. Watching them has captivated me since childhood. The episode in which Dubykky meets Jurgen after he tumbles from a tree derives from something I witnessed. I wish I could claim that I struck up a friendship with that crow, but I was at my family cabin and left soon after. (The crow, a fledgling, might have been too embarrassed for overtures anyhow.) I wrote up a description and thought about how to use it in a fiction. This was while I was just beginning Echoes.

As a supernatural being, Dubykky has to have at least one endearing, human-like trait that does not involve people. Otherwise, he would seem a mere parasite, or maybe symbiont. So, as a pirate has his parrot, I thought, Dubykky should have his crow, and I arranged the meeting. Then Junior comes along, and the poor kid needs a companion, and Dubykky shows a laudable compassion in lending him Jurgen.

Every morning I feed crows on the parking strip outside my kitchen. Jurgen and Yuki (see Rogues). They are namesakes.

BP: How would you describe some of the underlying thematic issues at play in this novel?

RAS: Echoes deifies evil while casting it as an exclusively human failing. It is an offense to homo sapiens and nature. The more narcissistic a person is allowed to become, the more likely he or she is to turn into a predator, and predators derange community.

William Dubykky personifies the fantasy component of the novel. Nature dispatches echoes to kill predators and prevent further damage to society, and he acts something like their job performance monitor. Beginning before Echoes opens, however, and continuing through the series, Dubykky finds himself drawn into human-like relationships and thereby comes to act more human. So the novels propose this as a corollary to the evil-is-antisocial theme: the opposite of evil is not an abstract good; good emerges from engagement with others for common benefit.

In this light the courtship of Milton Cledge and Mildred Warden exemplifies a kind of goodness, while that of Matt and Misty Gans depicts its perversion. Hans Berger’s withdrawal from society has resulted from war, the great failure of social interchange, and is pathetic. Junior’s ironic tragedy is that he could never offer his gifts to benefit society: his sweetness, lack of guile, concern for those under threat, and wonderment.

Dubykky’s belief that he has a duty to kill surviving echoes conflicts with his growing attachment to them, Junior in particular. He follows supernatural rules that he comes to dislike and doubt. This tension runs through the series.

BP: Echoes is the first installment of a trilogy. Without any plot spoilers, can you give readers a sense of what they can expect in the books to come?

RAS: Dubykky grows more human despite himself. He has to. The long era during which beings like him wreaked vengeance on aberrant humans is drawing to a close. Human society has become so complex, so interconnected, so lacking in privacy, that by and large its institutions can perform the task that echoes are created for. Although he remains steadfast in tracking down the last new echoes, Dubykky is becoming redundant.

Reconceiving his role entails unforeseen obligations to both echoes and non-echoes. His days as a lone wolf end. I think I’d better leave it at that, or else where is the fun in watching Dubykky/Devlin/Dantlyng succumb to what have been impossibilities for half a millennium? Among them, commitment, even an abrasive love.

BP: Who are some of your major literary influences?

If influence is calculated based on how many times one reads something, then for me Jane Austen’s Persuasion and Pride and Prejudice place first and second by a healthy margin. I have also, as I aged, been a fan of Lewis Carrol, Mark Twain, Robert Heinlein, Geoffrey Chaucer, John Steinbeck, V.S. Naipaul, Roberto Bolaño, Tim O’Brien, John Connolly, and Pat Barker. They’re in addition to other Great Tradition authors that I read in college, but how deeply does stuff that you parse out for class dig its claws into you?

RAS: What are you reading right now?

Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See and John Daniel’s Gifted. That’s beside background reading for a writing project, such as The Roadside Geology of Nevada (Frank DeCourten/Norma Biggar) and Turn this Water into Gold (John M. Townley).

Baobab Press

316 California Avenue, #24

Reno, Nevada 89509

info@baobabpress.com