Notes on The King’s Highway

There’s an old philosophical question that goes something like this: are people basically bad with a few good tendencies, or basically good with a few bad tendencies?

The King’s Highway is one small episode in one person’s years-long attempt to answer that question.

On the one hand, it’s not difficult to find uplifting stories in the news of selfless people rescuing people stuck in tubes, extracting babies from tubes, or opening peoples’ clogged airways with small tubes. (Apparently I can only think of tube-based emergencies just now.)

On the other hand, and I swear this is a true story, I once saw a woman literally poop onto a car because it was double parked and she couldn’t get out.

Now, ask yourself. Do those seem like the actions of someone who’s basically good? Do you detect even the faintest blush of basic goodness issuing forth from betwixt those two pink cheeks?

As a cartoonist, this enduring philosophical question poses two interrelated problems, one of substance and one of craft.

To wit, on the one hand, there are only so many tube-to-human encounters I wish to draw. On the other, no one wants to read a book full of (figurative, of course) car-poopery.

To put it slightly less grossly, it’s hard to write about humanity, its basic goodness or basic badness, and still be funny.

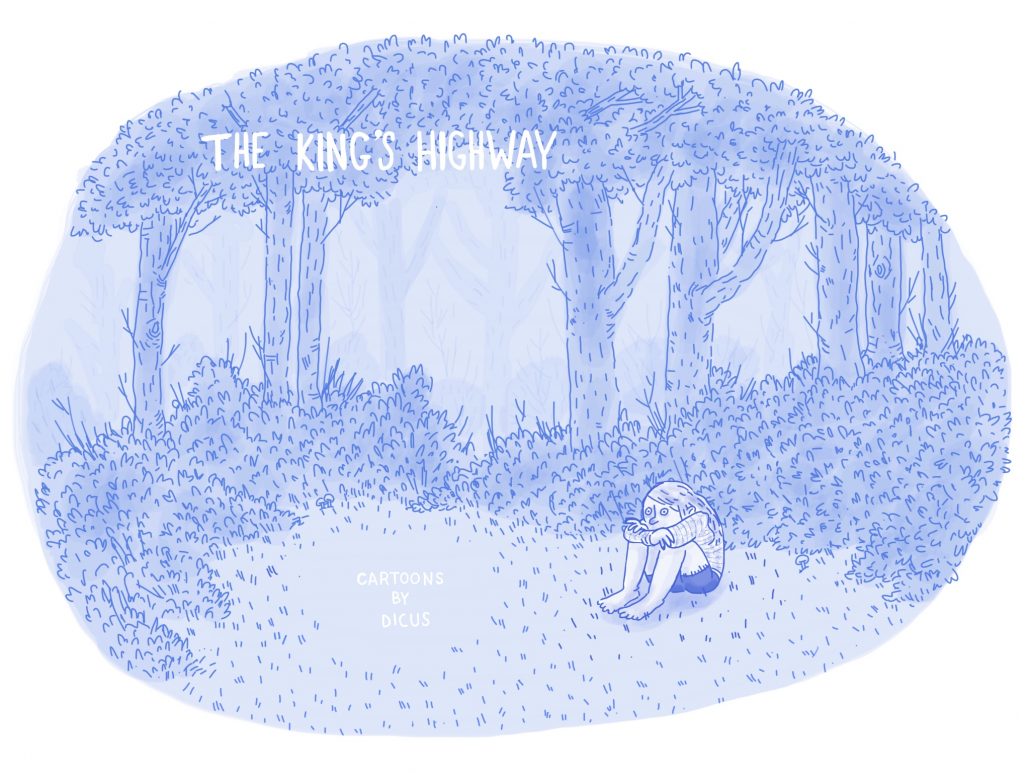

To show my cards somewhat, I’m not a very optimistic person, and it has been pointed out to me more than a few times that I have a slightly dark sense of humor. While some purveyors of comedy thrive in the dark side, it is risky territory, and anyone trying to strike the right balance between laugh-aloud satire and thought-provoking commentary might easily find himself or herself sinking into the numb, existential despair of a French pubescent in a silent film. Here, for example, is an actual rejected cover design for The King’s Highway.

The kind editors at Baobab Press, seeing this cover design, sat me down and calmly explained, the way one might explain to a geriatric monkey that buttons aren’t candy, that making people sad isn’t going to make them want to read a book of cartoons.

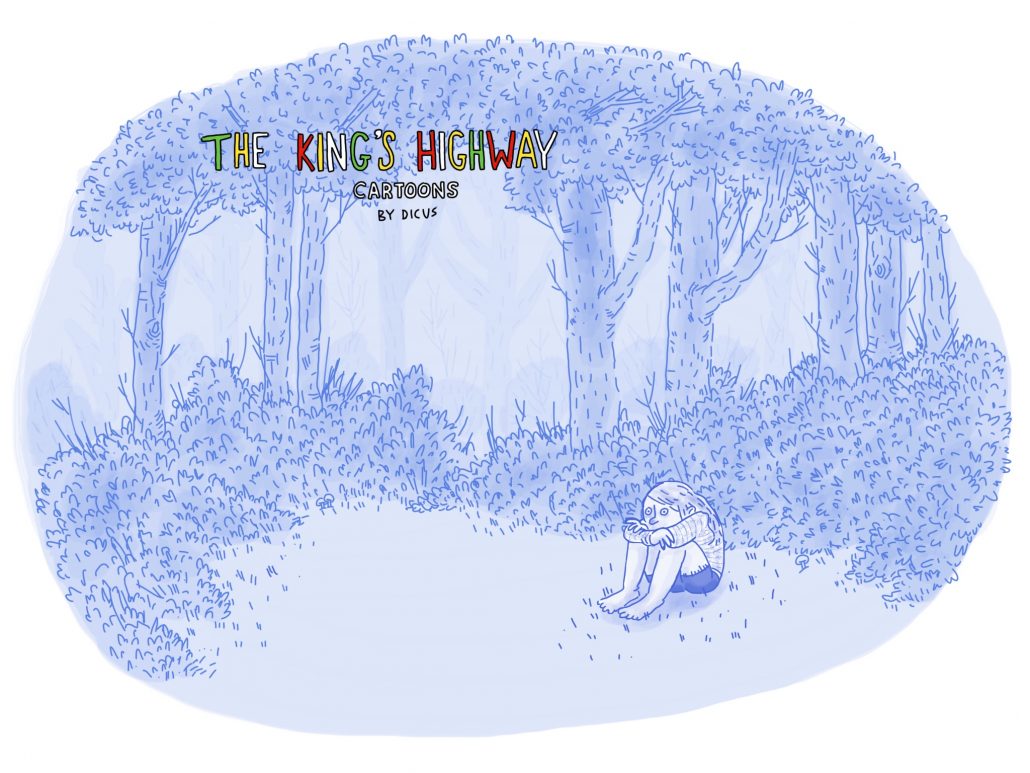

Taking their feedback to heart, I gave it another pass:

Clearly, some part of me thought that I could slap some clown colors on this Prozac ad and it would magically become funny. Obviously, not so. Back to the drawing board, to try to balance dark social satire with light-hearted laughs.

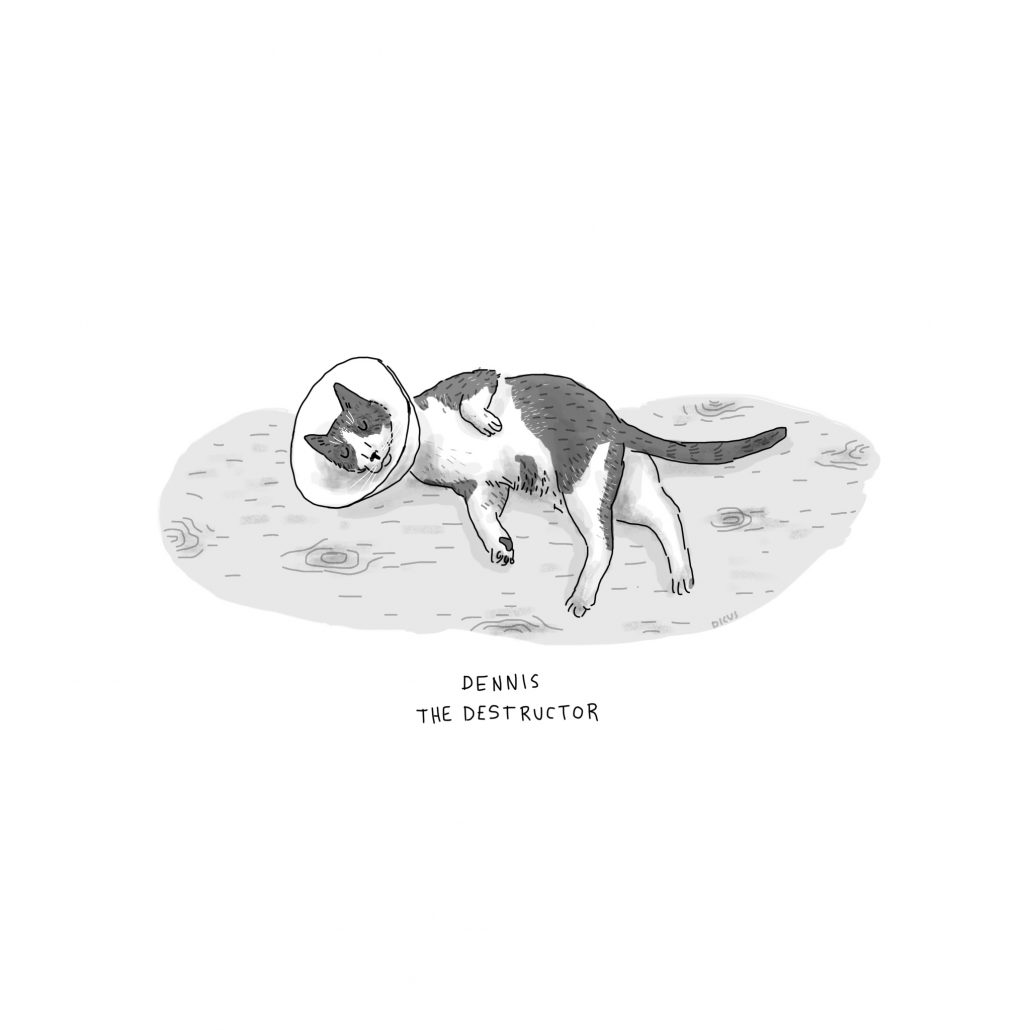

In some ways, as it turns out, I was looking too hard. The answer was, in fact, right in front of me the whole time. Specifically, a few inches in front of my face, licking itself and sneezing onto my sandwich. It was my cat, Dennis (who also, by the way, thinks he’s a dog).

Dennis is a cranky bastard who can yawn his rotten breath directly into your face, make you bleed profusely, dissect your brand new coat, and then immediately afterwards, somehow, make you belly-laugh. He has excellent comic timing, for one thing. Once, while looking particularly sweet, and while my wife and I were having a grave and hushed conversation about some of his many and serious health problems, my wife looked at him affectionately and let him know that he was loved. In response, he leaned close to her, his big eyes glistening, and he slapped her with two hands. Do you know how difficult it is for a cat to slap you with both forepaws? It takes a lot of effort and balance. A cat really needs a solid core to pull off a good two-hander. More importantly, a cat needs a comic style that is somehow both mean and hilarious in equal measure.

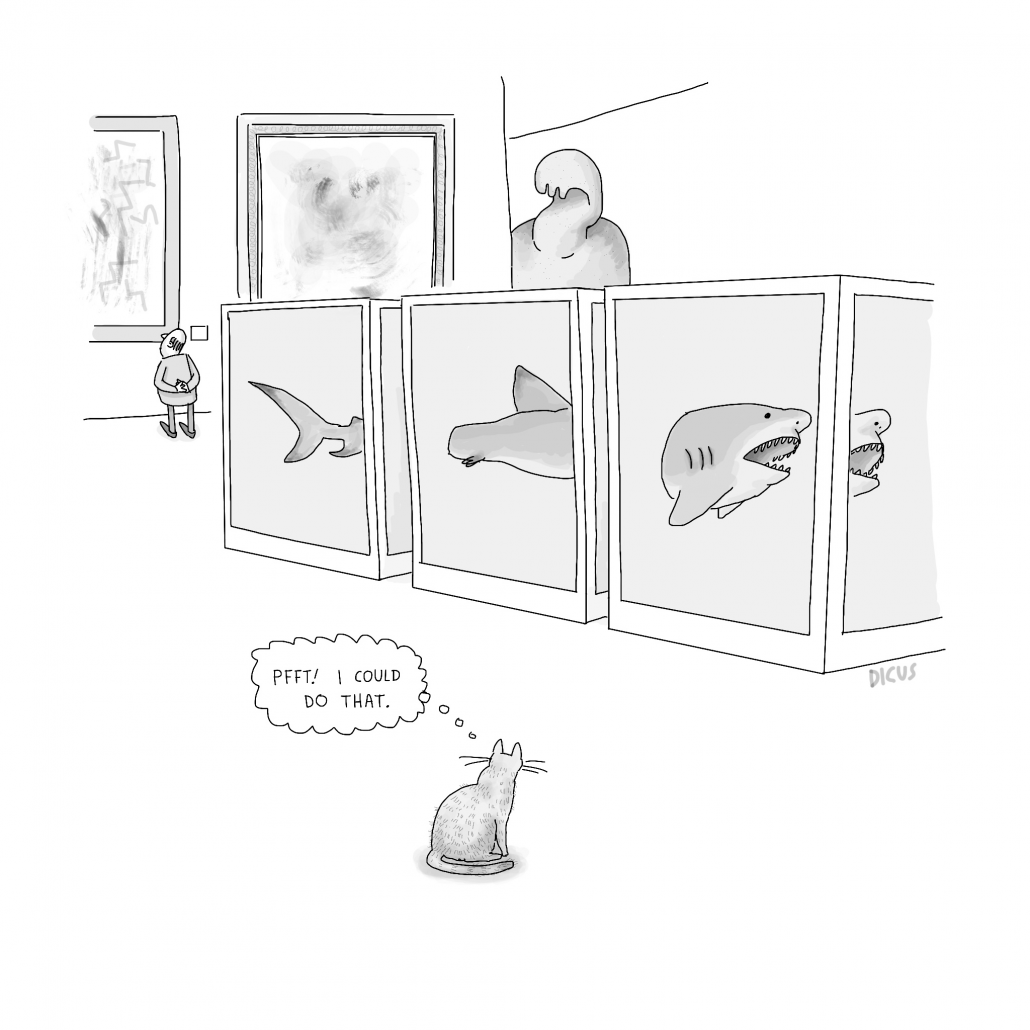

To take another example, framed pictures enrage Dennis. He has a fierce and irrational hatred of them.

If Dennis sees a new framed picture on the wall, he will cease all activity and become consumed with bloodlust. He will pause mid-stride, glare at it for a few pregnant moments, slowly boil with rage, and then, when it fails to retreat at the very sight of his mighty fury, he will dart across the room and hurl himself against the wall, claws-first, with what passes in cat-world for Spartan, self-sacrificing fortitude. He will then spend the next few years scratching at the wall in its vicinity, looking at it the way I might look at a burrito full of hairs. It’s more than a little destructive, yes, but it’s also super funny. And he knows it.

Everything Dennis does is either destructive or hilarious – mostly, it’s some mixture of both. Actually, just a look will do, usually: the vacant, blinking stare of an animal who just doesn’t comprehend what a couch is, what it means to buy one, why it ought not to be turned inside-out, and why the two red-faced bipeds that live with him are jabbering at him in shrill, elevated voices.

More to the point, Dennis has the at-times salty attitude of a human cartoonist trying to keep a sense of humor in a world full of people who are either tragically stuck in tubes or editorially pooping onto others’ cars.

In short, Dennis is a master of craft. He finds ways – however exaggerated and bizarre — to express his feelings about a world that he doesn’t understand and sometimes doesn’t like, but without being cruel or fatalistic. For all of his comic violence, Dennis knows he isn’t hurting anything, not really. He carries himself with a puckish glee that shows his destruction is always half-play, and more than a little fun.

So does Dennis think the world is basically good? Basically bad? Where does ol’ Dennis Sandwich Sneezer sit on the human nature debate? I suspect he has strong thoughts on the subject, actually. He may know better than me, in fact: there’s a kind of wisdom in cats (who think they’re dogs) who indulge in boiling rage in the most comical ways, only then to surrender to the simple pleasures of a patch of sunshine.

But he’s not telling. And that’s perhaps his most important lesson. Dennis lets us make up our own minds about how odious framed pictures are. And while he’s been generally successful in getting me to enjoy sunny days a little more, to make time for boxes once in a while, and to developing innovative ways of letting squirrels know that our fire escape is very much not their toilet, his greatest achievement, as far as I’m concerned, is getting me to notice ordinary, mundane things I normally wouldn’t — and to think about what those things, and my reactions to them, might say about a complex world and my feelings about it.

And, in my view, that’s exactly what good cartoons should do.